This eye-opening account describes daily life on a 19th-century army ship

8-9 minute read

By The Findmypast Team | September 10, 2020

Findmypast's military records expert, Paul Nixon made a fascinating find in our newspapers. A diary of one British soldier's experiences as he travelled overseas.

One of the attractions of joining the British Army has always been the opportunity to see the world and serve overseas. In the days of the Empire, maintaining a presence in the Dominions was an absolute necessity. For example, at the turn of the century, the British Army in India was around 180,000-strong. It consisted of professional soldiers who had done basic training in England and could now expect to spend most of their service overseas.

In February 1898, the Army and Navy Gazette published an interesting article on how soldier Tommy Atkins arrived at his overseas stations. The author of the article is unknown but it could have been Horace Wyndham who, as a gentleman ranker, enlisted in the army in 1890 and published an account of his time in scarlet and khaki in Soldiers of the Queen the following year. Having discovered the article, we reproduced an edited version below and it makes for a very revealing read. Enjoy.

Life on board a troop ship

“Ashore, Tommy Atkins is as familiar to us as the postman or the tax-collector, but it is with Tommy as a sailor that I propose to deal in this article.

The moment he leaves the train at Southampton and gets his accouterments aboard the transport, all the glamour with which we are accustomed to surrounding him fades away. He becomes quite an ordinary person, and his admirers who could see him doing fatigue duty on deck would scarcely recognize him.

It was in 1894 that the Government decided to do away with the five Indian troopers so well known in the Service and replace them by hired transports. These were chartered from the three largest shipping companies - the P and O, Cunard, and British India Companies who between them placed five vessels, the Victoria and Britannia (P and O), the Pavonia (Cunard), and the Dilwara and Jumna (British India) at the disposal of the Imperial authorities during the trooping season.

Setting sail

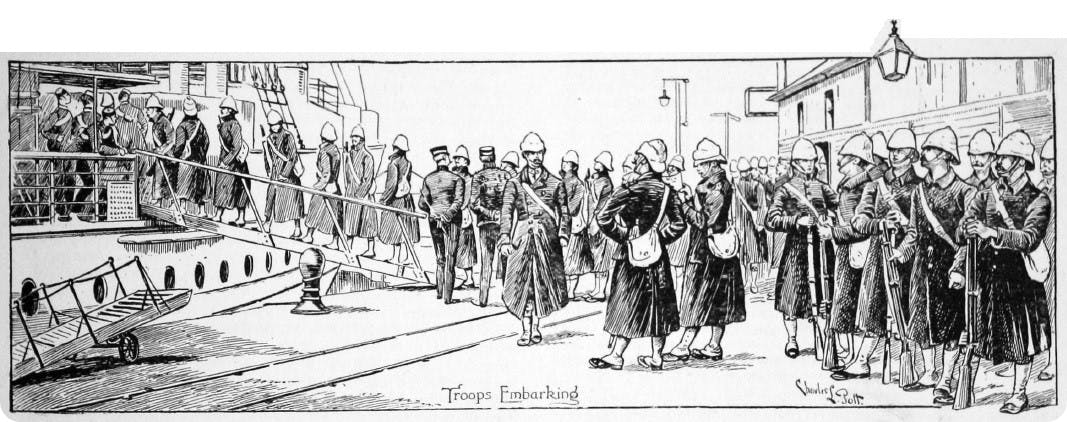

The departure is an interesting event and many sightseers, besides his relatives and the girl he is going to leave behind him, assemble at the wharf at Southampton to see the last of Tommy who has been ordered to India or the Cape.

That he does not look forward, with particularly pleasurable anticipations to his seven years' exile goes without saying. Stories told to him by time-expired soldiers of the agonies of sea-sickness, the heat of the climate, and the thought that he will not taste good honest roast beef and bitter beer until his return, all tend to dampen his ardor which up to his embarkation has been artificially stimulated by the farewell glasses of well-meaning friends.

Having left their belongings on board, the soldiers go ashore again to be told off to messes, each of which consists of 16 to 18 men. Once on board again, they are given a good square meal that would bring water to the mouth of a deep-sea sailor, every man sitting down to his food at the same time. Then an inspection of the ship is undertaken by the captain, a Naval officer, a staff officer, and the colonel commanding. The men are told off to fire and boat quarters. The arrangements in this particular have been so perfected by constant practice that the whole performance is gone through, for the first time, in half an hour. Armed men are stationed at the boats, to prevent any rushing in case of emergency and the strictest discipline is maintained throughout.

After this has been performed to the satisfaction of the officers, the bedding is served out, and so careless is Tommy of his belongings, that frequent inspection is found to be necessary to prevent him losing his blankets. Neatly fitted racks are made in the hammock-room for the storing of the bedding during the day and in addition to the non-commissioned officer in charge, a ship’s officer and a military officer are always present at the issuing and the taking in. A hammock and two blankets are served to the unmarried of the rank and file, while the sergeants and their wives and families are accommodated with beds.

When all the more important duties have been assigned to the 1,400 men who form the complement of a large transport, the fatigue duties are given out, which consist of cleaning the ship, on deck and down below, and other matters which Tommy, however industrious he may be ashore, simply abhors afloat.

The lifebelt parade is, perhaps, the only portion of the ship's routine that Tommy really takes any interest in. Besides being a novelty to him, it affords excellent material for chaff; and the comic artist (and there is often one among the men) invariably chooses the moment of life belts for his most scathing work. At the sound of the bugle, the men fall in, as if for parade. The belts are passed up by those stationed in the ladders, and within 14 minutes every Tommy on board has his belt on securely. Everyone in the ship, with the exception of the officers’ wives and invalids, is bound to have a belt on when the captain and colonel go round on their tour of inspection, and a sufficient number of belts are taken to the hospital and their use explained to the patients.

Day-to-day life

At 10:30 every morning an inspection of the ship is made by the captain, the colonel, adjutant, and military officer of the watch, during which every nook and cranny of the vessel, and all the mess utensils, are overhauled. This over, the troops - who have been paraded on the upper deck - are dismissed, and with the exception of those on guard, are at liberty to kill time as they please. And Tommy can kill time better than anyone I know. To most persons, a long sea voyage, even relieved by the various distractions provided, is more or less monotonous, but it is by no means so to Tommy.

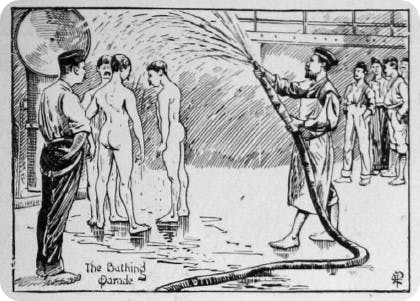

As a general rule, there is nothing he loves better than to loll about the deck. He has made up his mind for a good steady loaf when he gets on board, and manfully he sticks to his determination during the voyage. Some few regiments engage largely in calisthenic exercise. The adjutant of one regiment I sailed with used to rise every morning at 6 o'clock and make a number of his men go through all sorts of Sandow exercises (named after Friedrich Wilhelm Mulle, the father of modern bodybuilding) until nine. These men landed in the pink of condition.

During the fine weather, concerts are occasionally organized among the men. All sorts of amusements are supplied by the Government for the use of the troops, though the game that Tommy loves best is “lotto,” or, as he calls it, “ouse" - meaning, I suppose, “ house.” This game, which requires very little skill, is, as most of my readers are doubtless aware, played with numbered cards and counters. As Tommy always makes a strictly gambling game out of this, it is interdicted by Government, which is, I suppose, one of the reasons why he is so partial to it. He has a gamble whenever possible, quite content to risk the chance of punishment for his little bit of sport.

Keeping the troops in line

Talking of punishment reminds me that very little is generally required, and although cells are fitted up in all the transports, they are rarely used. Extra fatigues, the stoppage of their "baccy" or the compulsory answering to their names every hour when the bugle sounds, are usually quite sufficient punishments for the petty offenses that the newly-fledged soldiers commit on the outward voyage.

Homeward-bound men "doing time” for various offenses are closely confined, except for a short time daily, when they are escorted for exercise. The colonel of the regiment is, of course, the judge and jury, and justice is dispensed in a manner that would make some of our legal luminaries open their eyes.

Food and drink

One of the reasons for the orderly conduct of the troops during the voyage is the fact that no intoxicants are sold on board, except on the return trip, when a tot of rum is allowed at a penny a head. On arrival at the various ports of call, the troops are kept strictly to the ship, except at places like Cape Town, where they are marched for a few hours daily if the ship remains more than three days in port.

The outward-bound canteen is what Tommy calls a "dry" one, though lemonade and sherbet are sold, in addition to “extras," like jam and other dainties. Pickles, which seem to take Tommy’s fancy as a cure for seasickness, are retailed at one penny a small bottle.

The hours for meals on a transport will strike most late diners as peculiar. Breakfast is served at 7 am, dinner at noon, and supper at 4 pm. In cold weather, all the men are in bed by 8 pm and asleep by nine. They seem to be capable of putting in a good eight hours’ sleep, despite their snoozes during the day, and then turn out at reveille looking as if they had only had a few hours’ repose.

Sleeping arrangements

The warrant officers - the bandmasters, regimental sergeants, and schoolmasters are entitled to second-class fare, while the non-commissioned officers, the next in rank, are given what is termed class sixteen. The wives of the non-commissioned officers are berthed and messed in the class next to class sixteen. This accommodation is excellent.

Certain portions of the poop deck are marked out and allotted to the various grades, and I have seen more squabbles over these little squares than over anything else on board.

Ships of worship?

Each transport carries a Roman Catholic and a Protestant chaplain, who are considered sufficient to attend to the spiritual welfare of the troops, all of whom - with the exception of those sick or on duty - are compelled to attend the two services held on Sundays, and the prayers which are delivered at 9.45 am daily. It is no use Tommy declaring himself an Atheist. He would not be excused if he worshipped the sun or pinned his faith to a spook.

Creature comforts

Nearly every regiment possesses a private pet, which has very often to be left behind on embarkation, as the regulations on this subject are very strict. In India, Tommy keeps any number of pets, and on his return loves to bring a parrot with him. The regulations allow 25% of the men to bring home parrots and I have seen as many as 300 or more of these birds distributed about the deck.

No cavalry regiments, with the exception of those bound for the Cape, carry their horses with them and only the chargers of the colonel, the senior major, and the adjutant, besides the Government stud horses, accompany the soldiers on their outward voyage. For these, special grooms are carried, and one of these men is in attendance on his four-footed charges night and day.

Disembarking at their destination

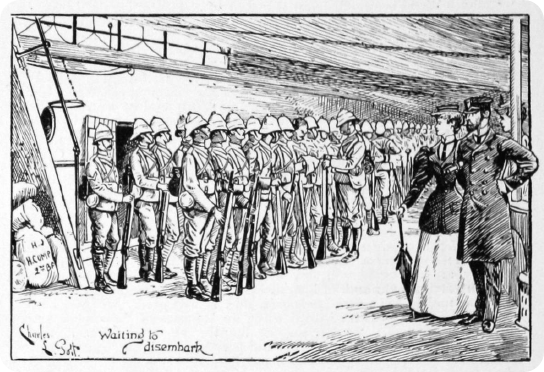

The transports generally arrive at their destination between the hours of 6 am and 8 am. On such occasions, the troops have to turn out at 4 am, return all the ship’s gear, pay for deficiencies, and prepare themselves for disembarkation. Naturally, the greatest bustle prevails but it is remarkable how quickly each soldier procures his own rifle, bayonet, and valise.

Once on land again, Tommy quickly becomes the smart, dapper fellow we know so well and soon forgets the trials and pleasures of the trip."

Did your ancestor cross the seas in service like Tommy? Delve into our travel and military records to discover their remarkable stories today.

Related articles recommended for you

Discover Home Children's stories

What's New?

Who Do You Think You Are? Series 21 lineup announced

Discoveries

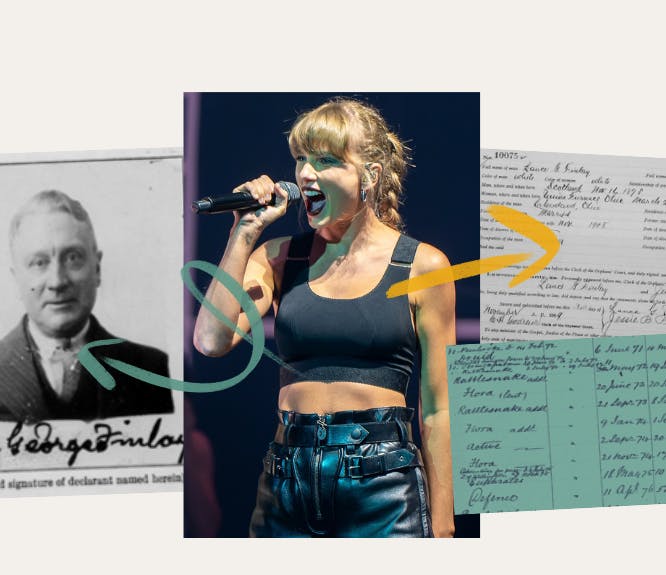

Taylor Swift’s family tree shines with love, heartbreak and the triumph of the human spirit

Discoveries